2024-11-04 14:35:00

arpitrage.substack.com

As housing affordability becomes a key political issue, the one rare area of apparent consensus is that large-scale institutional investors are to blame. For instance, Tim Walz highlighted this issue in the VP debate:

On housing, we could talk a little bit about Wall Street speculators buying up housing and making them less affordable.

This has led to proposed legislation targeting these investors, based on the idea they exercise market power and are bidding up house prices and rents. In some housing circles, the role of these investors (alongside the role of algorithms for price setting) are really viewed as the central drivers of housing unaffordability.

Are these reasonable views from an economist perspective? At first blush, the fact that these investors still own such a small fraction of the overall stock of single-family homes would suggest their impact is still pretty minor. But what accounts for the entry of these investors, and is their impact so far good or bad?

I have a great PhD student on the job market this year, Josh Coven, who has written a topical and well-executed Job Market Paper which sheds light on these issues, which I’ll summarize below.

The first thing to note about the rental landscape, especially the single-family rental world, is that it is pretty fragmented — you have a lot of mom-and-pop landlords who operate at a small scale. This started to change after the 2008 financial crisis, with the entry of large-scale landlords like Blackstone. At first, these investor groups targeted areas with high foreclosure rates, which allowed them to amass large portfolios at deep discounts.

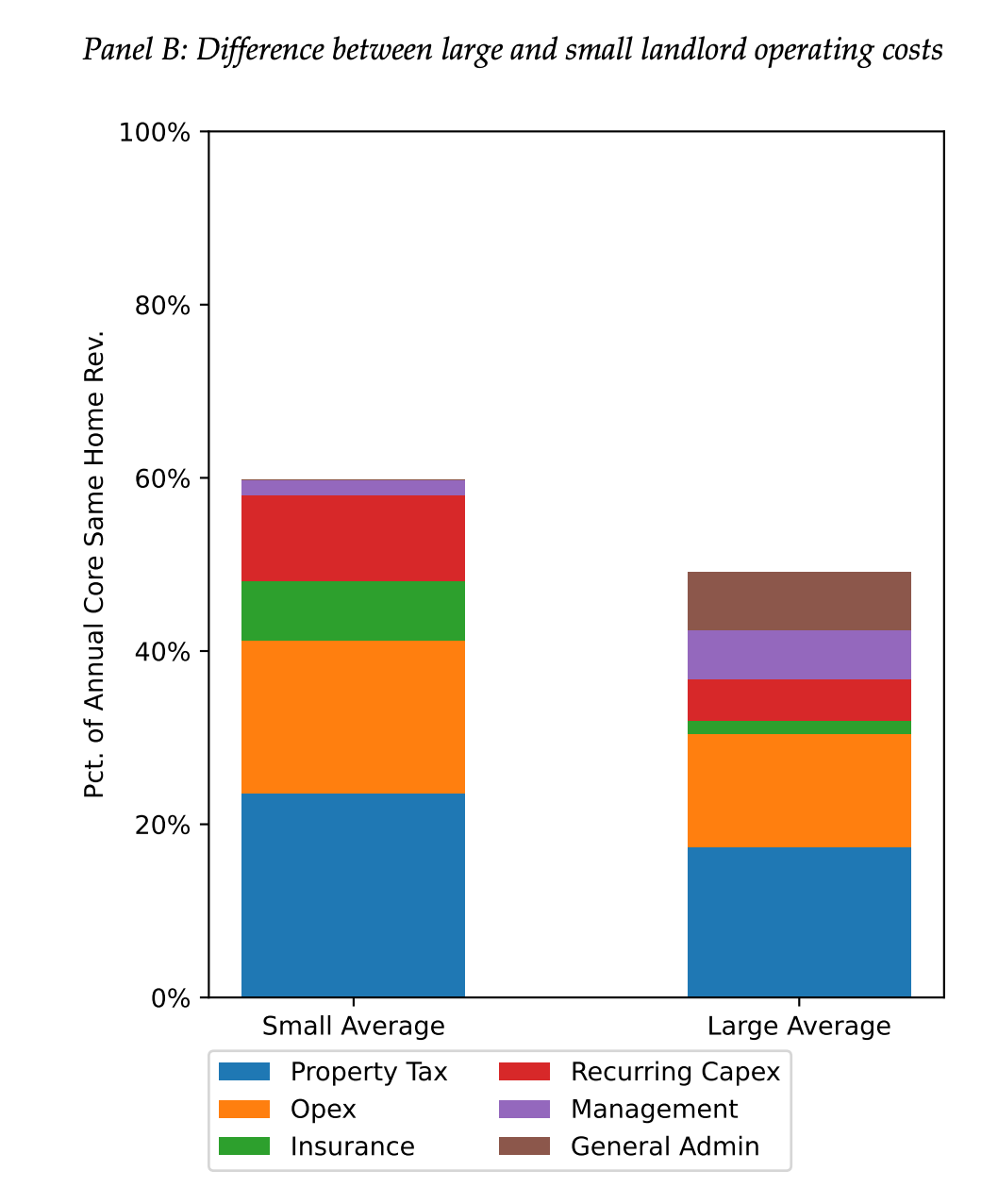

The key difference with these new large-scale investors is that new rental management technologies, financial instruments, and bargaining power allow Wall Street investors to operate with lower costs in levels and also exhibit much better economies of scale relative to the mom-and-pops.

Josh shows that large investors enjoy cost advantages by paying fewer operating expenses, property taxes, and lower mortgage costs. One particularly interesting one is insurance costs, which have of course been rising all over the country. Large landlords appear to enjoy bargaining advantages and pay substantially lower insurance expenses as well.

The only way that many small landlords can remain cost competitive is by avoiding mortgages and outside management companies entirely. However, this inherently limits the scale at which these landlords can operate, and these strategies are also pretty time-intensive. Those smaller landlords which do try to scale up (by taking out mortgages, etc.) quickly hit profitability barriers, and in fact Josh measures a surprising fraction of such landlords appear not to be profitable at all.

Professionalizing management, better bargaining over expenses, some degree of appeals over property tax, and better access to capital markets therefore enable institutional investors to improve their cost structure, which results in their ability to provide many rentals at scale. They are also able to maintain these lower costs even as the number of properties they manage goes up.

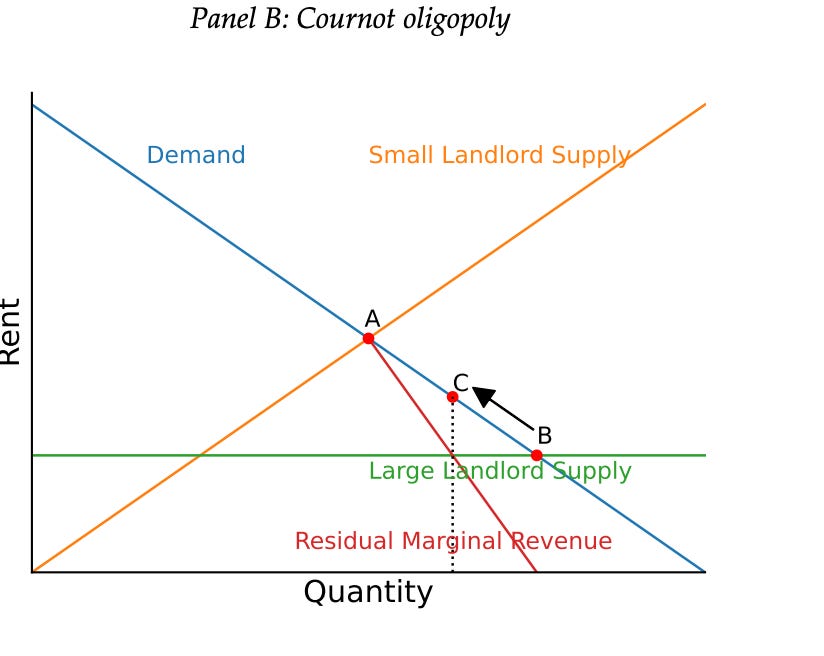

However, another consequence of this greater scale is large landlords do appear to have some market power, as they are the sole residual source of additional rental properties. So in the basic supply and demand graph above: large landlords have a flatter and lower supply curve (due to lower costs overall and flat marginal costs), which moves the housing market equilibrium from A to B. However, if they optimally exercise market power on the supply they provide above what small landlords can, the markets wind up at an equilibrium point C instead.

So both effects are going on here in this stylized model: institutional landlords are more efficient, and their ability to provide more rental properties lowers rents and increases rental availability. However, they take a fraction of the gains back as market power. Notably, renters still benefit overall from Wall Street investors, as rental availability and rents are still higher. One thing that’s going on here is that Wall Street investors help to arbitrage around financial frictions: many renters lack the down payments or credit scores to buy on their own, so they rent instead from an investor company who can buy and is renting out to them.

I think this gives you a sense of the key economics of the paper, though of course there is a lot more in there. Josh quantifies the intuition from the stylized setup with a much more detailed model featuring BLP estimation on the housing demand side, and a careful consideration of landlords as well. There are a number of important frictions to keep track of: there is a whole construction side of the model, in which builders respond to price signals, and a margin of adjustment between small and large landlords. All of these are important to get the quantification of investor impact right.

One important tradeoff in the model results is that institutional investors seem to improve outcomes for renters — who have better access to “high opportunity” neighborhoods characterized by better economic mobility and test scores, as well as lower rents overall — against higher prices for houses which make it harder for prospective homeowners.

But I want to focus on two key implications which get at the broader public debate over these investors. The first is about why people seem to care so much about these investors.

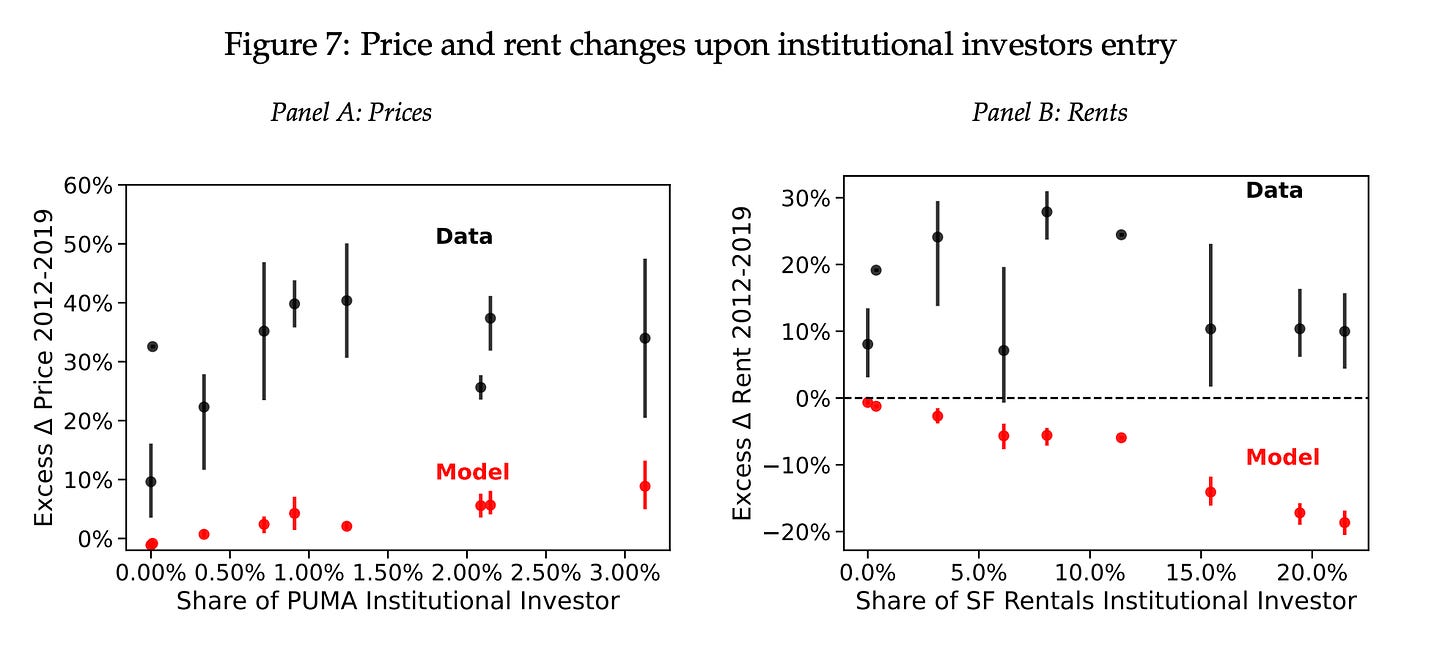

One key set of results Josh gets (Figure 7) is the relationship between institutional investor shares and prices/rents; both as observed in the data, compared to what the model predicts.

Essentially, the model suggests that house prices do rise a bit when Wall Street investors enter, but the effect is fairly modest. Two key reasons for this are 1) housing supply responds a bit to institutional investor entry, and 2) investors partially crowd out mom-and-pop landlords. Both of these effects mean that when institutional investors buy homes, they don’t reduce the availability for owners 1-1, and so the price effects are muted as well. And, of course, the model actually predicts a decline in rents.

By contrast, you see that house prices and rents went up quite a bit, in actuality, in areas where Wall Street landlords entered. So to the casual observer, it looks as if the entry of institutional investors is driving really enormous price action.

What is happening here, basically, is the standard economic story of selection: consistent with Josh’s modeling of them, institutional investors are picking areas likely to see future rental growth. Therefore, even if their own actions slightly lower rental pressures, it’s going to look as if they correlate with higher house prices and rents. It’s sort of a similar situation as housing supply skeptics who don’t believe that new housing supply can reduce rents due to some sort of folk economics-OLS.

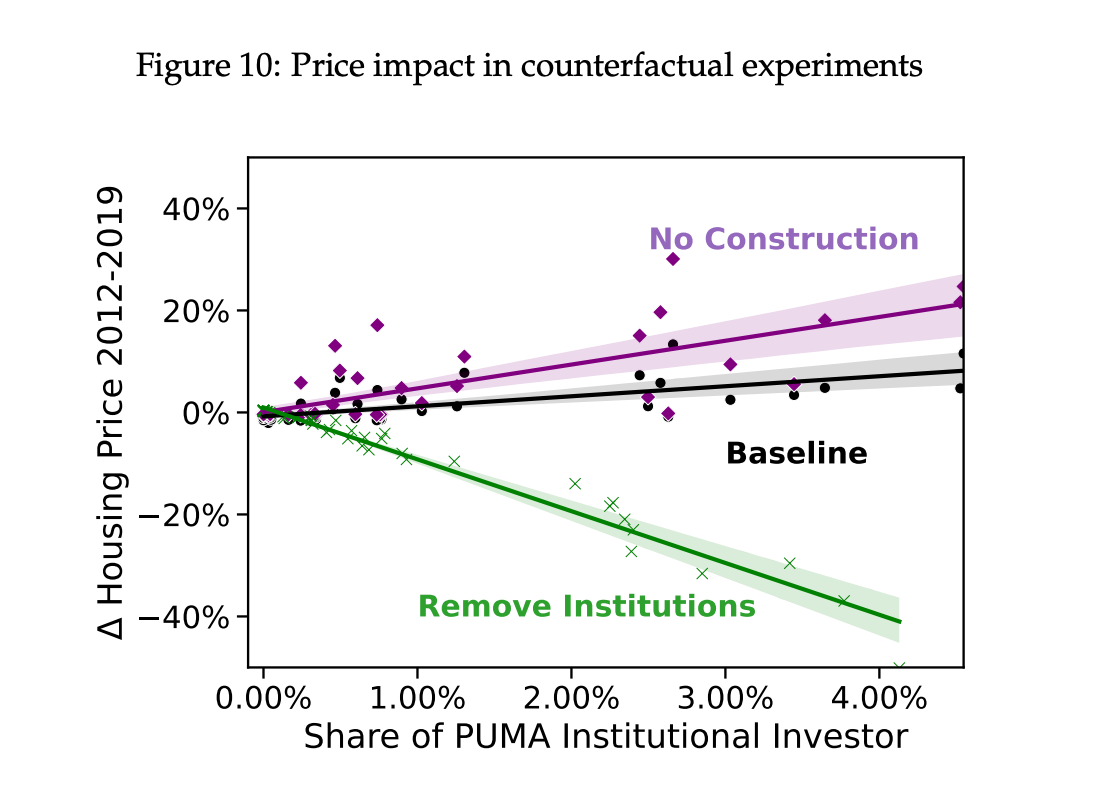

The discussion above suggests that housing supply is a key part of how we assess the impact of institutional investors. Indeed, as many have recognized, landlords themselves emphasize these factors, ie Blackstone’s Jonathan Gray:

The one benefit to existing owners is that construction lending is getting tighter. I think we will see less new supply and long-term that’s a positive… Fundamentals around supply and demand are what drives value. That’s why I have confidence going forward

Josh simulates some of these changes in counterfactual simulations. A world without housing supply responses would feature even higher price impact from the entry of institutional investors. By the same token, policymakers concerned about the impact of these investors on homeownership and house prices can increase housing supply, which strongly mitigates those consequences while preserving the benefits of these investors for renters.

Of course, another way to mitigate these impacts is for institutional investors to build housing themselves. This kind of build-to-rent market seems to be growing quite quickly, and can be another important way to address housing shortfalls without crowding out homeownership.

I hope this gives you a flavor for the paper — again, there is a lot of other stuff there, so be sure to check it out (and interview Josh!).

Support Techcratic

If you find value in Techcratic’s insights and articles, consider supporting us with Bitcoin. Your support helps me, as a solo operator, continue delivering high-quality content while managing all the technical aspects, from server maintenance to blog writing, future updates, and improvements. Support Innovation! Thank you.

Bitcoin Address:

bc1qlszw7elx2qahjwvaryh0tkgg8y68enw30gpvge

Please verify this address before sending funds.

Bitcoin QR Code

Simply scan the QR code below to support Techcratic.

Please read the Privacy and Security Disclaimer on how Techcratic handles your support.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, Techcratic may earn from qualifying purchases.

![Unsolved Mysteries: UFOs [DVD]](https://techcratic.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/516SW6A0RVL-345x180.jpg)