2024-11-07 00:27:00

nfil.dev

I’ve been reading up on the Double Ratchet algorithm and its implementations lately, as it’s an exciting piece of crypto that offers some very nice guarantees: forward secrecy (ie. by breaking a key at some point you can’t read older messages), eventual break-in recovery (ie. by breaking a key you can only read a few messages before the protocol recovers), and of course confidentiality and deniability. It’s all done through the use of “ratchets”, which are used to update the key used with each message. The algorithm comes at a nice time, when consumers are becoming more privacy-aware and governments more determined to perform mass surveillance, which is where E2E encryption becomes the only way to protect your data.

Double Ratchet is used by the biggest platforms in the field, such as Signal, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp and Matrix in order to provide E2E encryption for their instant messages. To clear that up, as I was wondering about this myself, this means that each message is encrypted on the client: If you’re using a web client then Javascript is doing the encrypting and decrypting. The keys are never supposed to leave your device, though most platforms actually store them for you in practice and you simply encrypt the keys with another key and store that instead. That’s because the browser has a low capacity for websites to store data, and there’s more key material to store than you might expect.

This concept was not the easiest to wrap my head around, as with my limited knowledge of crypto I had to often pause and thing why something works while to someone with more experience it might have been obvious. The Double Ratchet and X3DH specs were of course my main reading materials. Luckily they’re much simpler to follow than I expected and I was able to implement the basics of the spec. There are also some very helpful videos by Computerphile that explain the algorithm in a nice, visual way.

There’s no better way to understand something than to make it yourself. Plus crypto code is so fun to write. Maybe because it’s so wrong to do your own crypto? Maybe because you feel like a math genius when you get the message decrypted successfully? We will never know. So, here’s my attempt at implementing both the key exchange and messaging parts while explaining what’s happening along the way.

Double Ratchet? How about a single one?

First of all, some context: A ratchet is a structure that updates with each message sent, providing a new key. This is a “turn” of the ratchet: A single turn generates a new key, part of which is used as the new ratchet state and part of which is the output of the ratchet, to be used for encrypting messages. By having a pre-shared secret key, the two parties (Alice and Bob, per tradition) can initialize their ratchet structures so that they can deduce the same keys and therefore read each other’s encrypted messages. A ratchet only turns one way: previous keys cannot be deduced even if an attacker manages to obtain the state of the ratchet at some point. Future ones however can.

This is augmented by using a second ratchet, which gives the algorithm its name. That ratchet provides new ephemeral Diffie-Hellman shared secrets which are then used to initialize the previous ratchet’s state. By doing that, Alice and Bob can ensure that an attacker who has obtained the first ratchet’s state will not be able to follow along and decrypt more messages once this DH exchange has occurred. This provides the algorithm with eventual break-in recovery.

Key exchange using Extended Triple Diffie-Hellman

The Extended Triple Diffie-Hellman (or X3DH) algorithm is used to establish the initial shared secret key between Alice and Bob, based on their public keys and using a server. Bob has already published some information on a server and Alice wants to establish a shared secret key with Bob in order to send him an encrypted message, while Bob is not online. Alice must therefore be able to perform the key exchange using simply the information stored on the server. The server can also be used to store messages by either of them until the other one can retrieve them.

Bob needs to generate several X25519 key pairs ahead of time:

IK_bis Bob’s long-term identity key. It is published to the server and is used to identify Bob.SPK_bis Bob’s signed pre-key. The public key is published along with the signatureSig(IK_b, SPK_b)using Bob’s identity key, therefore proving that Bob has access to the private key ofIK_b. This key should be re-generated and updated by Bob every few weeks or months in order to provide better forward secrecy.OPK_b,OPK_b',OPK_b''… are Bob’s one-time pre-keys. Each one’s public key is published to the server and can be fetched by another party who wishes to communicate with Bob, after which it is deleted from the server. He can have as many as he wishes up to a limit defined by the server.

Similarly, Alice must generate and own the following:

IK_ais Alice’s long-term identity key. It is published to the server and is used to identify Alice.EK_ais Alice’s ephemeral key which is generated simply for the upcoming DH with Bob’s keys.

Alice then downloads a bundle from the server, which includes Bob’s identity public key, signed public pre-key and its signature, and one of Bob’s public pre-keys.

Alice must know, of course, that the public key she received belongs to the person she wants to talk to in order to prevent a MITM attack. This must be done out-of-band. For example, Alice might ask Bob for his public key offline and store that.

Then, she verifies the downloaded signature using IK_b. If the signature matches she can go ahead with establishing the secret. She calculates the following four secret outputs, using Diffie-Hellman:

DH1=DH(IK_a, SPK_b)DH2=DH(EK_a, IK_b)DH3=DH(EK_a, SPK_b)DH4=DH(EK_a, OPK_b)

In short, the following DH exchanges happen:

The first two of these secrets provide mutual authentication: The identity keys of both parties are used in them. Therefore if one of the parties tries to use a different identity key, they will arrive at a different result. The last two of these secrets provide forward secrecy as they are unique to this exchange.

By concatenating the four secrets and applying a KDF Alice arrives at the shared key that will be later used to initialize her ratchets. For the KDF I’m using HKDF per the spec, with empty salt and info parameters for simplicity.

SK = KDF(DH1 || DH2 || DH3 || DH4)

Afterwards, Alice sends Bob the public key of EK_a via the server, as well as her public identity key IK_a and the identifier of Bob’s one-time pre-key that she used (OPK_b). She also sends him the first encrypted message: IK_a || IK_b, which Bob will use to verify the identity keys of both parties.

Once Bob comes online, he will know one of his one-time pre-keys has been used by Alice to establish a new shared key. He will fetch IK_a and EK_a from the server. He must also know that IK_a belongs to the real Alice as well, as stated before. As he knows the private components of IK_b, SPK_b and OPK_b he can perform the same Diffie-Hellman calculations as Alice did using her public keys, and should therefore arrive at the same SK as Alice.

Let’s put all that into code. First, all of the imports we will need:

# Requirements:

# apt install python3 python3-pip

# pip3 install cryptography==2.8 pycrypto

import base64

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives import hashes, serialization

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives.asymmetric.x25519 import X25519PrivateKey

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives.asymmetric.ed25519 import \

Ed25519PublicKey, Ed25519PrivateKey

from cryptography.hazmat.primitives.kdf.hkdf import HKDF

from cryptography.hazmat.backends import default_backend

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

Then we can make the Bob and Alice classes. We skip the server for simplicity and assume they just communicate everything through it. I also skipped the verification of SPK_b’s signature as I couldn’t find a python library for it.

def b64(msg):

# base64 encoding helper function

return base64.encodebytes(msg).decode('utf-8').strip()

def hkdf(inp, length):

# use HKDF on an input to derive a key

hkdf = HKDF(algorithm=hashes.SHA256(), length=length, salt=b'',

info=b'', backend=default_backend())

return hkdf.derive(inp)

class Bob(object):

def __init__(self):

# generate Bob's keys

self.IKb = X25519PrivateKey.generate()

self.SPKb = X25519PrivateKey.generate()

self.OPKb = X25519PrivateKey.generate()

def x3dh(self, alice):

# perform the 4 Diffie Hellman exchanges (X3DH)

dh1 = self.SPKb.exchange(alice.IKa.public_key())

dh2 = self.IKb.exchange(alice.EKa.public_key())

dh3 = self.SPKb.exchange(alice.EKa.public_key())

dh4 = self.OPKb.exchange(alice.EKa.public_key())

# the shared key is KDF(DH1||DH2||DH3||DH4)

self.sk = hkdf(dh1 + dh2 + dh3 + dh4, 32)

print('[Bob]\tShared key:', b64(self.sk))

class Alice(object):

def __init__(self):

# generate Alice's keys

self.IKa = X25519PrivateKey.generate()

self.EKa = X25519PrivateKey.generate()

def x3dh(self, bob):

# perform the 4 Diffie Hellman exchanges (X3DH)

dh1 = self.IKa.exchange(bob.SPKb.public_key())

dh2 = self.EKa.exchange(bob.IKb.public_key())

dh3 = self.EKa.exchange(bob.SPKb.public_key())

dh4 = self.EKa.exchange(bob.OPKb.public_key())

# the shared key is KDF(DH1||DH2||DH3||DH4)

self.sk = hkdf(dh1 + dh2 + dh3 + dh4, 32)

print('[Alice]\tShared key:', b64(self.sk))

alice = Alice()

bob = Bob()

# Alice performs an X3DH while Bob is offline, using his uploaded keys

alice.x3dh(bob)

# Bob comes online and performs an X3DH using Alice's public keys

bob.x3dh(alice)

As suspected, the key exchange works! Here’s a sample input so far.

[Alice] Shared key: 6SJPsg17ocf4N/rY7TFf3KSEQr5iavhv7P5TJylNWU0=

[Bob] Shared key: 6SJPsg17ocf4N/rY7TFf3KSEQr5iavhv7P5TJylNWU0=

Symmetric Ratchet

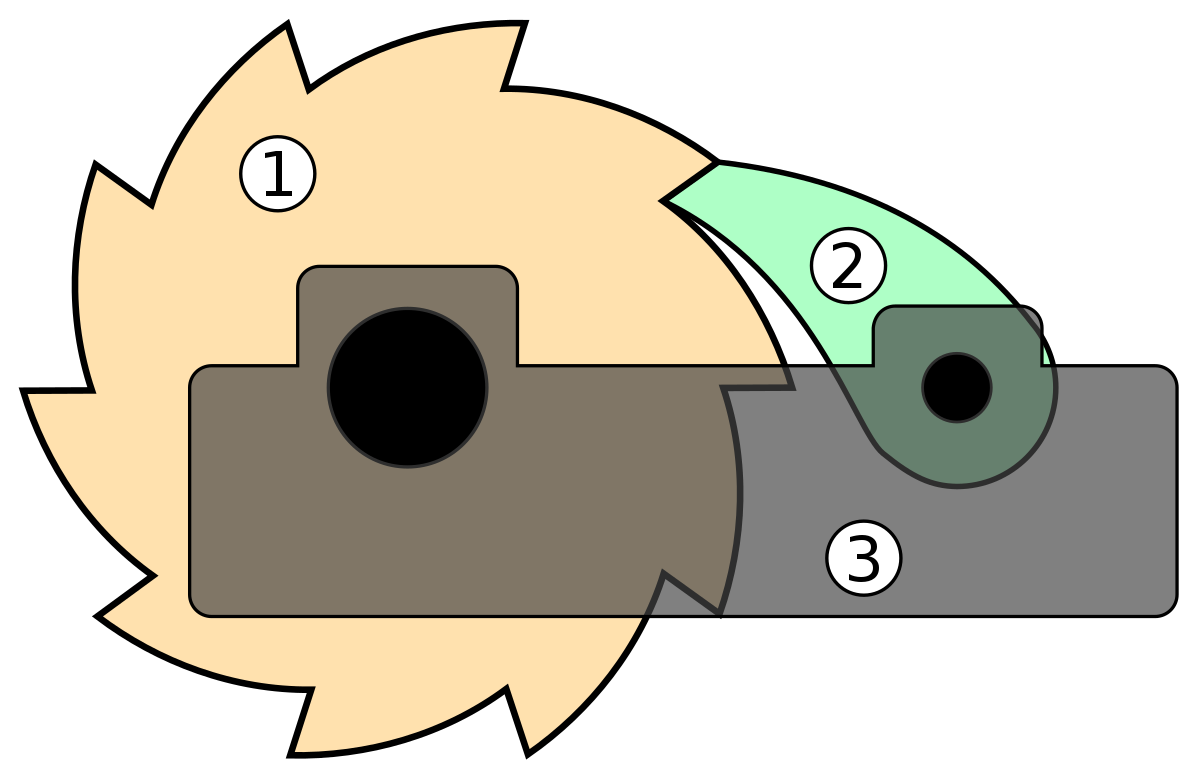

The symmetric ratchet is the first ratchet type that we discussed before. The symmetric ratchet is implemented with a KDF chain using the HKDF algorithm, which ensures that the output will be cryptographically secure.

On the initial step, the KDF function is supplied with a secret key and some input data, which can be a constant. The output of the KDF is another secret key. This new key is split into two parts: The next KDF key and the message key. This is a turn of the “ratchet”: The internal state of the ratchet (the KDF key) is changed and a new message key is created.

Because the output of the KDF algorithm is cryptographically secure, it’s hard to reconstruct the input key of the KDF given the output key. This means that an attacker can’t reconstruct older keys even if the current state and message key is leaked. They can however decrypt a single message by using the message key. In addition, by changing the input parameter on each step, we are also guaranteed break-in recovery: An attacker can’t deduce the next state of the ratchet by only knowing the current state if they don’t know what the input is. If the input is constant however an attacker can sync with the ratchet and decrypt all future messages.

Having performed the X3DH algorithm, both Alice and Bob have now arrived at a common shared secret key. That is now used to establish their session keys by using the Double Ratchet algorithm.

Each of them maintains three symmetric ratchets in order to be able to communicate. The first one is the root ratchet. This ratchet is initialized with the shared key of Alice and Bob. The input of this ratchet can be assumed to be constant for now, which however does not provide break-in recovery. This will change in the next section.

The other two ratchets are the sending and receiving ratchets. Alice’s sending ratchet’s state must always match Bob’s receiving ratchet state, and vice-versa. These two ratchets are both initialized from the first two keys provided by the root chain. When Alice wants to send a message to Bob, she turns her sending ratchet once, obtaining a new message key. She then encrypts her message using that message key.

Similarly, Bob initializes his sending and receiving ratchets by turning his root ratchet twice. When he receives a message from Alice he turns his receiving ratchet once, matching the state of Alice’s sending ratchet. This provides him with the key to decrypt the message. He can send messages to Alice in a similar fashion, using his sending ratchet and Alice’s receiving ratchet.

By having two separate ratchets for sending and receiving, we make sure that Bob and Alice won’t have an issue of both claiming the same key from their ratchets and sending each other a message at the same time. Each message is also accompanied by the order that it was sent. This way, if Bob receives a message out of order, he can turn his receiving ratchet more than once to get the appropriate message key to decrypt it. He also stores the message keys that he skipped in case these messages arrive, so that he can then decrypt them.

Let’s add a simple ratchet implementation to our code, and the initialization methods to Bob and Alice.

class SymmRatchet(object):

def __init__(self, key):

self.state = key

def next(self, inp=b''):

# turn the ratchet, changing the state and yielding a new key and IV

output = hkdf(self.state + inp, 80)

self.state = output[:32]

outkey, iv = output[32:64], output[64:]

return outkey, iv

class Bob(object):

# snip

def init_ratchets(self):

# initialise the root chain with the shared key

self.root_ratchet = SymmRatchet(self.sk)

# initialise the sending and recving chains

self.recv_ratchet = SymmRatchet(self.root_ratchet.next()[0])

self.send_ratchet = SymmRatchet(self.root_ratchet.next()[0])

class Alice(object):

# snip

def init_ratchets(self):

# initialise the root chain with the shared key

self.root_ratchet = SymmRatchet(self.sk)

# initialise the sending and recving chains

self.send_ratchet = SymmRatchet(self.root_ratchet.next()[0])

self.recv_ratchet = SymmRatchet(self.root_ratchet.next()[0])

alice = Alice()

bob = Bob()

# Alice performs an X3DH while Bob is offline, using his uploaded keys

alice.x3dh(bob)

# Bob comes online and performs an X3DH using Alice's public keys

bob.x3dh(alice)

# Initialize their symmetric ratchets

alice.init_ratchets()

bob.init_ratchets()

# Print out the matching pairs

print('[Alice]\tsend ratchet:', list(map(b64, alice.send_ratchet.next())))

print('[Bob]\trecv ratchet:', list(map(b64, bob.recv_ratchet.next())))

print('[Alice]\trecv ratchet:', list(map(b64, alice.recv_ratchet.next())))

print('[Bob]\tsend ratchet:', list(map(b64, bob.send_ratchet.next())))

Success! This is our new output:

[Alice] send ratchet: ['+/6Gq39lwvg3JQAvl3HxrLmebInwzdqy6w+rGFWlzpw=', 'J47otn/26gEdpT8/o0FDDw==']

[Bob] recv ratchet: ['+/6Gq39lwvg3JQAvl3HxrLmebInwzdqy6w+rGFWlzpw=', 'J47otn/26gEdpT8/o0FDDw==']

[Alice] recv ratchet: ['E/7OUo7RGn7GDv8VDhc26avKOvwCTAIX1xH9krYeF6w=', 'q9pdP023Z0nerNVH9xrrsg==']

[Bob] send ratchet: ['E/7OUo7RGn7GDv8VDhc26avKOvwCTAIX1xH9krYeF6w=', 'q9pdP023Z0nerNVH9xrrsg==']

We can see their send and recv ratchets outputs match. This is of course because we initialized Alice’s sending ratchet first, but Bob’s second. This is not arbitrary – it depends on who sends the message as we’ll see in a bit, who we’ve been assuming is Alice in this case.

You might also observe there’s two outputs, while we expected one. That’s because the second one will be used as the IV for encrypting messages.

Alice and Bob have estabished a session now. They could now use these to send each other messages with proven confidentiality, integrity, authentication and forward secrecy, rotating the appropriate ratchet after sending or receiving a message. It does not however provide break-in recovery, as an attacker can still guess the future states of the sending or receiving ratchet if their state is leaked, or can deduce the states of both if the shared secret key of the root ratchet is leaked. This is why there’s our other type of ratchet: The Diffie-Hellman ratchet.

Diffie-Hellman Ratchet

The second ratchet type is the Diffie-Hellman ratchet which is used to reset the keys used for the sending and receiving ratchets of both parties to new values.

Before receiving a message from Alice, Bob must initialize a new ratchet key pair RK_b and advertise the public key to Alice. Upon learning Bob’s public key, Alice will then generate her own key pair RK_a and calculate DH(RK_a, RK_b). This value will be used as the input to turn Alice’s root symmetric ratchet once, yielding a new key. This key will then be used to initialize Alice’s sending symmetric ratchet.

The next message that Alice sends to Bob will be encrypted with a message key that comes from this sending ratchet. Therefore she must also advertise her new public key alongside this message, otherwise Bob will not be able to decode the message itself as he does not yet know the public key of RK_a. Once obtaining it, he can also calculate DH(RK_a, RK_b) and use that as input to his own root symmetric ratchet. As the state of his root ratchet must match Alice’s root ratchet before this step, the output of his root ratchet will be the new key for his receiving symmetric ratchet which must also match Alice’s sending ratchet. Then, this ratchet will generate a new message key which he can use to decrypt Alice’s message.

Next, Bob can introduce a new key pair RK_b'. Using Alice’s previous public key he calculates DH(RK_b', RK_a) and uses that as input to his root chain to get a new key for initializing his sending ratchet. He can now discard his old key pair. When he sends his new message, encrypted with the sending ratchet, he advertises his new public key. Alice can then once again calculate DH(RK_a, RK_b') to update her receiving ratchet and decrypt Bob’s message, and can proceed with introducing her own new key pair.

Note that the input values for the sending and receiving ratchets are still constant. The input value for the root symmetric ratchet is, however, the output value of the DH ratchet. This way we now also ensure eventual break-in recovery: Even if the state of a ratchet is leaked to an attacker, we will soon afterwards perform a turn of the DH ratchet and the symmetric ratchets will be reset to new, unknown to the attacker values.

This process signifies a single turn of the DH ratchet, as in each step one party’s key is renewed and the old one is forgotten. It can be performed as often as the two parties like in order to provide break-in recovery. In practice it’s done with every single message.

With that, we can add the code for maintaining the DH ratchet by both Bob and Alice. We don’t need a new construct for the DH ratchet, as it’s sufficient to keep an X25519 key pair for each user.

class Bob(object):

def __init__(self):

# snip

# initialise Bob's DH ratchet

self.DHratchet = X25519PrivateKey.generate()

def dh_ratchet(self, alice_public):

# perform a DH ratchet rotation using Alice's public key

dh_recv = self.DHratchet.exchange(alice_public)

shared_recv = self.root_ratchet.next(dh_recv)[0]

# use Alice's public and our old private key

# to get a new recv ratchet

self.recv_ratchet = SymmRatchet(shared_recv)

print('[Bob]\tRecv ratchet seed:', b64(shared_recv))

# generate a new key pair and send ratchet

# our new public key will be sent with the next message to Alice

self.DHratchet = X25519PrivateKey.generate()

dh_send = self.DHratchet.exchange(alice_public)

shared_send = self.root_ratchet.next(dh_send)[0]

self.send_ratchet = SymmRatchet(shared_send)

print('[Bob]\tSend ratchet seed:', b64(shared_send))

class Alice(object):

def __init__(self):

# snip

# Alice's DH ratchet starts out uninitialised

self.DHratchet = None

def dh_ratchet(self, bob_public):

# perform a DH ratchet rotation using Bob's public key

if self.DHratchet is not None:

# the first time we don't have a DH ratchet yet

dh_recv = self.DHratchet.exchange(bob_public)

shared_recv = self.root_ratchet.next(dh_recv)[0]

# use Bob's public and our old private key

# to get a new recv ratchet

self.recv_ratchet = SymmRatchet(shared_recv)

print('[Alice]\tRecv ratchet seed:', b64(shared_recv))

# generate a new key pair and send ratchet

# our new public key will be sent with the next message to Bob

self.DHratchet = X25519PrivateKey.generate()

dh_send = self.DHratchet.exchange(bob_public)

shared_send = self.root_ratchet.next(dh_send)[0]

self.send_ratchet = SymmRatchet(shared_send)

print('[Alice]\tSend ratchet seed:', b64(shared_send))

alice = Alice()

bob = Bob()

# Alice performs an X3DH while Bob is offline, using his uploaded keys

alice.x3dh(bob)

# Bob comes online and performs an X3DH using Alice's public keys

bob.x3dh(alice)

# Initialize their symmetric ratchets

alice.init_ratchets()

bob.init_ratchets()

# Initialise Alice's sending ratchet with Bob's public key

alice.dh_ratchet(bob.DHratchet.public_key())

Bob can’t yet however decrypt Alice’s message! He also needs to turn his own DH ratchet, and that depends on Alice’s public key, which she must send along with her message. Let’s implement both their send and recv methods.

def pad(msg):

# pkcs7 padding

num = 16 - (len(msg) % 16)

return msg + bytes([num] * num)

def unpad(msg):

# remove pkcs7 padding

return msg[:-msg[-1]]

class Bob(object):

#snip

def send(self, alice, msg):

key, iv = self.send_ratchet.next()

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv).encrypt(pad(msg))

print('[Bob]\tSending ciphertext to Alice:', b64(cipher))

# send ciphertext and current DH public key

alice.recv(cipher, self.DHratchet.public_key())

def recv(self, cipher, alice_public_key):

# receive Alice's new public key and use it to perform a DH

self.dh_ratchet(alice_public_key)

key, iv = self.recv_ratchet.next()

# decrypt the message using the new recv ratchet

msg = unpad(AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv).decrypt(cipher))

print('[Bob]\tDecrypted message:', msg)

class Alice(object):

# snip

def send(self, bob, msg):

key, iv = self.send_ratchet.next()

cipher = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv).encrypt(pad(msg))

print('[Alice]\tSending ciphertext to Bob:', b64(cipher))

# send ciphertext and current DH public key

bob.recv(cipher, self.DHratchet.public_key())

def recv(self, cipher, bob_public_key):

# receive Bob's new public key and use it to perform a DH

self.dh_ratchet(bob_public_key)

key, iv = self.recv_ratchet.next()

# decrypt the message using the new recv ratchet

msg = unpad(AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv).decrypt(cipher))

print('[Alice]\tDecrypted message:', msg)

alice = Alice()

bob = Bob()

# Alice performs an X3DH while Bob is offline, using his uploaded keys

alice.x3dh(bob)

# Bob comes online and performs an X3DH using Alice's public keys

bob.x3dh(alice)

# Initialize their symmetric ratchets

alice.init_ratchets()

bob.init_ratchets()

# Initialise Alice's sending ratchet with Bob's public key

alice.dh_ratchet(bob.DHratchet.public_key())

# Alice sends Bob a message and her new DH ratchet public key

alice.send(bob, b'Hello Bob!')

# Bob uses that information to sync with Alice and send her a message

bob.send(alice, b'Hello to you too, Alice!')

Finally, this is the output of the program:

[Alice] Send ratchet seed: vBwolG3I276Krq85ykTHdAlVjJMD+s1zACNqk+0BNyI=

[Alice] Sending ciphertext to Bob: vDT2BR/r00LIAVLbdhwpKw==

[Bob] Recv ratchet seed: vBwolG3I276Krq85ykTHdAlVjJMD+s1zACNqk+0BNyI=

[Bob] Send ratchet seed: qJQFz20nSyy0dSvDm1LtJj3LyEUcBMRSKZvAJeXpzYI=

[Bob] Decrypted message: b'Hello Bob!'

[Bob] Sending ciphertext to Alice: Qma+DBBwlVaCQNKaSRBfRIfXw1L3X1KsX/h1IMeWMxk=

[Alice] Recv ratchet seed: qJQFz20nSyy0dSvDm1LtJj3LyEUcBMRSKZvAJeXpzYI=

[Alice] Send ratchet seed: GzOTsxpBFbzSkKL6iY1IWjilL6+UStA3iMWoUSjBGRo=

[Alice] Decrypted message: b'Hello to you too, Alice!'

The message is being encrypted, sent over the server to Bob along with Alice’s DH ratchet public key. Bob uses that information to update his receiving chain so that he can decrypt the message. He then goes on to turn his own DH ratchet, updating his sending chain, and sends a reply back to Alice along with his new public key. Alice can then do the same process to decrypt her received message and send a new one of her own.

Conclusions

Hope I did a good job of explaining this, and you were able to follow along! I ignored many of the finer details, such as out-of-order messages, rooms with multiple users etc. However I believe the code is enough to demonstrate the elegance of the algorithm in a few lines and to provide a simple working example.

Support Techcratic

If you find value in Techcratic’s insights and articles, consider supporting us with Bitcoin. Your support helps me, as a solo operator, continue delivering high-quality content while managing all the technical aspects, from server maintenance to blog writing, future updates, and improvements. Support Innovation! Thank you.

Bitcoin Address:

bc1qlszw7elx2qahjwvaryh0tkgg8y68enw30gpvge

Please verify this address before sending funds.

Bitcoin QR Code

Simply scan the QR code below to support Techcratic.

Please read the Privacy and Security Disclaimer on how Techcratic handles your support.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, Techcratic may earn from qualifying purchases.