2024-11-30 02:34:00

twobithistory.org

The ARPANET changed computing forever by proving that computers of wildly

different manufacture could be connected using standardized protocols. In my

post on the historical significance of the ARPANET, I mentioned a few of those protocols, but didn’t

describe them in any detail. So I wanted to take a closer look at them. I also

wanted to see how much of the design of those early protocols survives in the

protocols we use today.

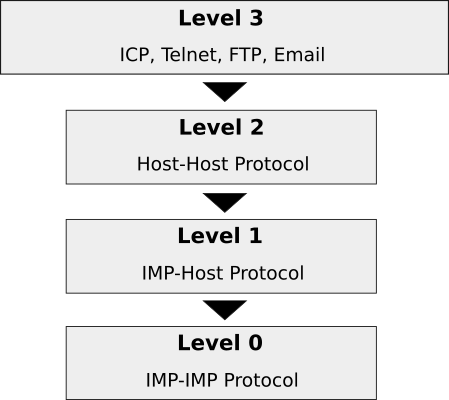

The ARPANET protocols were, like our modern internet protocols, organized into

layers. The protocols in the higher layers ran on top of the protocols in

the lower layers. Today the TCP/IP suite has five layers (the Physical,

Link, Network, Transport, and Application layers), but the ARPANET had only

three layers—or possibly four, depending on how you count them.

I’m going to explain how each of these layers worked, but first an aside about

who built what in the ARPANET, which you need to know to understand why the

layers were divided up as they were.

Some Quick Historical Context

The ARPANET was funded by the US federal government, specifically the Advanced

Research Projects Agency within the Department of Defense (hence the name

“ARPANET”). The US government did not directly build the network; instead, it

contracted the work out to a Boston-based consulting firm called Bolt, Beranek,

and Newman, more commonly known as BBN.

BBN, in turn, handled many of the responsibilities for implementing the network

but not all of them. What BBN did was design and maintain a machine known as

the Interface Message Processor, or IMP. The IMP was a customized Honeywell

minicomputer, one of which was delivered to each site across the country that

was to be connected to the ARPANET. The IMP served as a gateway to the ARPANET

for up to four hosts at each host site. It was basically a router. BBN

controlled the software running on the IMPs that forwarded packets from IMP to

IMP, but the firm had no direct control over the machines that would connect to

the IMPs and become the actual hosts on the ARPANET.

The host machines were controlled by the computer scientists that were the end

users of the network. These computer scientists, at host sites across the

country, were responsible for writing the software that would allow the hosts

to talk to each other. The IMPs gave hosts the ability to send messages to each

other, but that was not much use unless the hosts agreed on a format to use for

the messages. To solve that problem, a motley crew consisting in large part of

graduate students from the various host sites formed themselves into the

Network Working Group, which sought to specify protocols for the host computers

to use.

So if you imagine a single successful network interaction over the ARPANET,

(sending an email, say), some bits of engineering that made the interaction

successful were the responsibility of one set of people (BBN), while other

bits of engineering were the responsibility of another set of people (the

Network Working Group and the engineers at each host site). That organizational

and logistical happenstance probably played a big role in motivating the

layered approach used for protocols on the ARPANET, which in turn influenced

the layered approach used for TCP/IP.

Okay, Back to the Protocols

The ARPANET protocol hierarchy.

The protocol layers were organized into a hierarchy. At the very bottom was

“level 0.” This is the layer that in some sense doesn’t count, because on

the ARPANET this layer was controlled entirely by BBN, so there was no need

for a standard protocol. Level 0 governed how data passed between

the IMPs. Inside of BBN, there were rules governing how IMPs did this; outside

of BBN, the IMP sub-network was a black box that just passed on any data

that you gave it. So level 0 was a layer without a real protocol, in the sense

of a publicly known and agreed-upon set of rules, and its existence could be

ignored by software running on the ARPANET hosts. Loosely speaking, it handled

everything that falls under the Physical, Link, and Internet layers of the

TCP/IP suite today, and even quite a lot of the Transport layer, which is

something I’ll come back to at the end of this post.

The “level 1” layer established the interface between the ARPANET hosts and the

IMPs they were connected to. It was an API, if you like, for the black box

level 0 that BBN had built. It was also referred to at the time as the IMP-Host

Protocol. This protocol had to be written and published because, when the

ARPANET was first being set up, each host site had to write its own software to

interface with the IMP. They wouldn’t have known how to do that unless BBN gave

them some guidance.

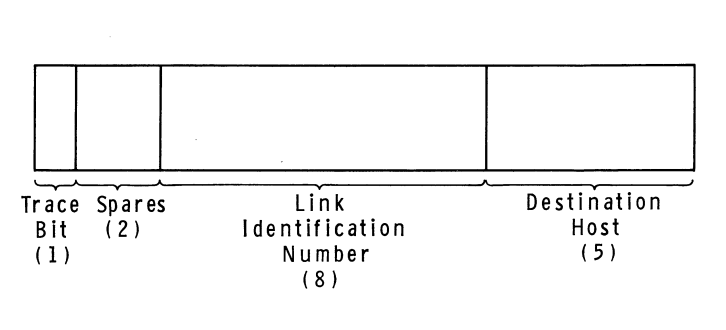

The IMP-Host Protocol was specified by BBN in a lengthy document called BBN

Report 1822. The

document was revised many times as the ARPANET evolved; what I’m going to

describe here is roughly the way the IMP-Host protocol worked as it was

initially designed. According to BBN’s rules, hosts could pass messages to

their IMPs no longer than 8095 bits, and each message had a leader that

included the destination host number and something called a link number.

The IMP would examine the designation host number and then dutifully forward

the message into the network. When messages were received from a remote host,

the receiving IMP would replace the destination host number with the source

host number before passing it on to the local host. Messages were not actually

what passed between the IMPs themselves—the IMPs broke the messages down into

smaller packets for transfer over the network—but that detail was hidden from

the hosts.

The Host-IMP message leader format, as of 1969. Diagram from BBN Report

1763.

The link number, which could be any number from 0 to 255, served two purposes.

It was used by higher level protocols to establish more than one channel of

communication between any two hosts on the network, since it was conceivable

that there might be more than one local user talking to the same destination

host at any given time. (In other words, the link numbers allowed communication

to be multiplexed between hosts.) But it was also used at the level 1 layer to

control the amount of traffic that could be sent between hosts, which was

necessary to prevent faster computers from overwhelming slower ones. As

initially designed, the IMP-Host Protocol limited each host to sending just one

message at a time over each link. Once a given host had sent a message along a

link to a remote host, it would have to wait to receive a special kind of

message called an RFNM (Request for Next Message) from the remote IMP

before sending the next message along the same link. Later revisions to this

system, made to improve performance, allowed a host to have up to eight

messages in transit to another host at a given time.

The “level 2” layer is where things really start to get interesting, because it

was this layer and the one above it that BBN and the Department of Defense left

entirely to the academics and the Network Working Group to invent for

themselves. The level 2 layer comprised the Host-Host Protocol, which was first

sketched in RFC 9 and first officially specified by RFC 54. A more readable

explanation of the Host-Host Protocol is given in the ARPANET Protocol

Handbook.

The Host-Host Protocol governed how hosts created and managed connections

with each other. A connection was a one-way data pipeline between a write

socket on one host and a read socket on another host. The “socket” concept

was introduced on top of the limited level-1 link facility (remember that the

link number can only be one of 256 values) to give programs a way of addressing

a particular process running on a remote host. Read sockets were even-numbered

while write sockets were odd-numbered; whether a socket was a read socket or a

write socket was referred to as the socket’s gender. There were no “port

numbers” like in TCP. Connections could be opened, manipulated, and closed by

specially formatted Host-Host control messages sent between hosts using link 0,

which was reserved for that purpose. Once control messages were exchanged over

link 0 to establish a connection, further data messages could then be sent

using another link number picked by the receiver.

Host-Host control messages were identified by a three-letter mnemonic. A

connection was established when two hosts exchanged a STR (sender-to-receiver)

message and a matching RTS (receiver-to-sender) message—these control messages

were both known as Request for Connection messages. Connections could be closed

by the CLS (close) control message. There were further control messages that

changed the rate at which data messages were sent from sender to receiver,

which were needed to ensure again that faster hosts did not overwhelm slower

hosts. The flow control already provided by the level 1 protocol was apparently

not sufficient at level 2; I suspect this was because receiving an RFNM from a

remote IMP was only a guarantee that the remote IMP had passed the message on

to the destination host, not that the host had fully processed the message.

There was also an INR (interrupt-by-receiver) control message and an INS

(interrupt-by-sender) control message that were primarily for use by

higher-level protocols.

The higher-level protocols all lived in “level 3”, which was the Application

layer of the ARPANET. The Telnet protocol, which provided a virtual teletype

connection to another host, was perhaps the most important of these protocols,

but there were many others in this level too, such as FTP for transferring

files and various experiments with protocols for sending email.

One protocol in this level was not like the others: the Initial Connection

Protocol (ICP). ICP was considered to be a level-3 protocol, but really it was

a kind of level-2.5 protocol, since other level-3 protocols depended on it. ICP

was needed because the connections provided by the Host-Host Protocol at level

2 were only one-way, but most applications required a two-way (i.e.

full-duplex) connection to do anything interesting. ICP specified a two-step

process whereby a client running on one host could connect to a long-running

server process on another host. The first step involved establishing a one-way

connection from the server to the client using the server process’ well-known

socket number. The server would then send a new socket number to the client

over the established connection. At that point, the existing connection would

be discarded and two new connections would be opened, a read connection based

on the transmitted socket number and a write connection based on the

transmitted socket number plus one. This little dance was a necessary prelude

to most things—it was the first step in establishing a Telnet connection, for

example.

That finishes our ascent of the ARPANET protocol hierarchy. You may have been

expecting me to mention a “Network Control Protocol” at some point. Before I

sat down to do research for this post and my last one, I definitely thought

that the ARPANET ran on a protocol called NCP. The acronym is occasionally used

to refer to the ARPANET protocols as a whole, which might be why I had that

idea. RFC 801, for example, talks about

transitioning the ARPANET from “NCP” to “TCP” in a way that makes it sound like

NCP is an ARPANET protocol equivalent to TCP. But there has never been a

“Network Control Protocol” for the ARPANET (even if Encyclopedia Britannica

thinks so), and I suspect people

have mistakenly unpacked “NCP” as “Network Control Protocol” when really it

stands for “Network Control Program.” The Network Control Program was the

kernel-level program running in each host responsible for handling network

communication, equivalent to the TCP/IP stack in an operating system today.

“NCP”, as it’s used in RFC 801, is a metonym, not a protocol.

A Comparison with TCP/IP

The ARPANET protocols were all later supplanted by the TCP/IP protocols (with

the exception of Telnet and FTP, which were easily adapted to run on top of

TCP). Whereas the ARPANET protocols were all based on the assumption that the

network was built and administered by a single entity (BBN), the TCP/IP

protocol suite was designed for an inter-net, a network of networks where

everything would be more fluid and unreliable. That led to some of the more

immediately obvious differences between our modern protocol suite and the

ARPANET protocols, such as how we now distinguish between a Network layer and a

Transport layer. The Transport layer-like functionality that in the ARPANET was

partly implemented by the IMPs is now the sole responsibility of the hosts at

the network edge.

What I find most interesting about the ARPANET protocols though is how so much

of the transport-layer functionality now in TCP went through a janky

adolescence on the ARPANET. I’m not a networking expert, so I pulled out my

college networks textbook (Kurose and Ross, let’s go), and they give a pretty

great outline of what a transport layer is responsible for in general. To

summarize their explanation, a transport layer protocol must minimally do the

following things. Here segment is basically equivalent to message as the

term was used on the ARPANET:

- Provide a delivery service between processes and not just host machines

(transport layer multiplexing and demultiplexing) - Provide integrity checking on a per-segment basis (i.e. make sure there is no

data corruption in transit)

A transport layer could also, like TCP does, provide reliable data transfer,

which means:

- Segments are delivered in order

- No segments go missing

- Segments aren’t delivered so fast that they get dropped by the receiver (flow

control)

It seems like there was some confusion on the ARPANET about how to do

multiplexing and demultiplexing so that processes could communicate—BBN

introduced the link number to do that at the IMP-Host level, but it turned out

that socket numbers were necessary at the Host-Host level on top of that

anyway. Then the link number was just used for flow control at the IMP-Host

level, but BBN seems to have later abandoned that in favor of doing flow

control between unique pairs of hosts, meaning that the link number started out

as this overloaded thing only to basically became vestigial. TCP now uses port

numbers instead, doing flow control over each TCP connection separately. The

process-process multiplexing and demultiplexing lives entirely inside TCP and

does not leak into a lower layer like on the ARPANET.

It’s also interesting to see, in light of how Kurose and Ross develop the ideas

behind TCP, that the ARPANET started out with what Kurose and Ross would call a

strict “stop-and-wait” approach to reliable data transfer at the IMP-Host

level. The “stop-and-wait” approach is to transmit a segment and then refuse to

transmit any more segments until an acknowledgment for the most recently

transmitted segment has been received. It’s a simple approach, but it means

that only one segment is ever in flight across the network, making for a very

slow protocol—which is why Kurose and Ross present “stop-and-wait” as merely a

stepping stone on the way to a fully featured transport layer protocol. On the

ARPANET, “stop-and-wait” was how things worked for a while, since, at the

IMP-Host level, a Request for Next Message had to be received in response to

every outgoing message before any further messages could be sent. To be fair to

BBN, they at first thought this would be necessary to provide flow control

between hosts, so the slowdown was intentional. As I’ve already mentioned, the

RFNM requirement was later relaxed for the sake of better performance, and the

IMPs started attaching sequence numbers to messages and keeping track of a

“window” of messages in flight in the more or less the same way that TCP

implementations do today.

So the ARPANET showed that communication between heterogeneous computing systems

is possible if you get everyone to agree on some baseline rules. That is, as

I’ve previously argued, the ARPANET’s most important legacy. But what I hope

this closer look at those baseline rules has revealed is just how much the

ARPANET protocols also influenced the protocols we use today. There was

certainly a lot of awkwardness in the way that transport-layer responsibilities

were shared between the hosts and the IMPs, sometimes redundantly. And it’s

really almost funny in retrospect that hosts could at first only send each

other a single message at a time over any given link. But the ARPANET

experiment was a unique opportunity to learn those lessons by actually building

and operating a network, and it seems those lessons were put to good use when

it came time to upgrade to the internet as we know it today.

If you enjoyed this post, more like it come out every four weeks! Follow

@TwoBitHistory

on Twitter or subscribe to the

RSS feed

to make sure you know when a new post is out.

Previously on TwoBitHistory…

Trying to get back on this horse!

My latest post is my take (surprising and clever, of course) on why the ARPANET was such an important breakthrough, with a fun focus on the conference where the ARPANET was shown off for the first time:https://t.co/8SRY39c3St

— TwoBitHistory (@TwoBitHistory) February 7, 2021

Keep your files stored safely and securely with the SanDisk 2TB Extreme Portable SSD. With over 69,505 ratings and an impressive 4.6 out of 5 stars, this product has been purchased over 8K+ times in the past month. At only $129.99, this Amazon’s Choice product is a must-have for secure file storage.

Help keep private content private with the included password protection featuring 256-bit AES hardware encryption. Order now for just $129.99 on Amazon!

Support Techcratic

If you find value in Techcratic’s insights and articles, consider supporting us with Bitcoin. Your support helps me, as a solo operator, continue delivering high-quality content while managing all the technical aspects, from server maintenance to blog writing, future updates, and improvements. Support Innovation! Thank you.

Bitcoin Address:

bc1qlszw7elx2qahjwvaryh0tkgg8y68enw30gpvge

Please verify this address before sending funds.

Bitcoin QR Code

Simply scan the QR code below to support Techcratic.

Please read the Privacy and Security Disclaimer on how Techcratic handles your support.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, Techcratic may earn from qualifying purchases.

![[Designed for Microsoft Surface] Cable Matters Desk Mount for Microsoft Surface…](https://techcratic.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/517TT-COFQL._AC_SL1500_-360x180.jpg)