2024-12-22 06:49:00

corelatus.com

Decoding the telephony signals in Pink Floyd’s ‘The Wall’

Posted December 4th 2024

I like puzzles. Recently, someone asked me to identify the telephone

network signalling in The Wall, a 1982 film featuring Pink

Floyd. The signalling is audible when the main character, Pink,

calls London from a payphone in Los Angeles,

in this

scene (Youtube).

Here’s a five second audio clip from when Pink calls:

What’s in the clip?

The clip starts with some speech overlapping a dial-tone which in

turn overlaps some rapid tone combinations, a ring tone and some

pops, clicks and music. It ends with an answer tone.

The most characteristic part is the telephone number encoded in the

rapid tone combinations. Around 1980, when the film was made,

different parts of the world used similar, but incompatible,

tone-based signalling schemes. They were all based on the same idea:

there are six or eight possible tones, and each digit is represented

by a combination of two tones.

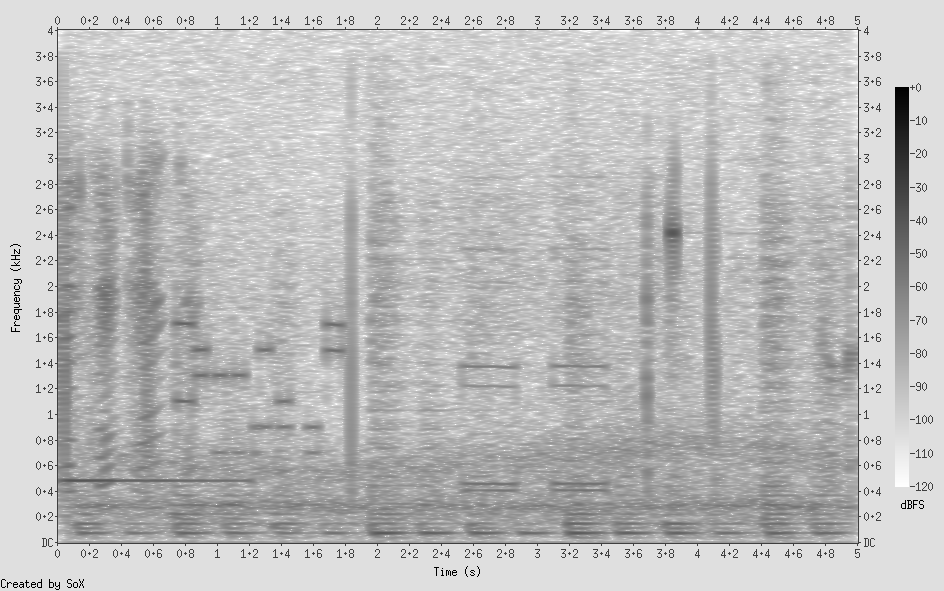

Let’s examine a spectrogram

SoX, an audio editing tool for PCs, can make charts that

show the spectral components of the audio over time. The horizontal

axis represents time, the vertical axis frequency, and darker

sections show more audio power, and lighter sections less.

Signalling tones appear as dark horizontal lines in the spectrogram,

with the digit signalling visible from 0.7 to 1.8 seconds. That part

of the signalling has tones at roughly 700, 900, 1100, 1300, 1500

and 1700 Hz.

Which signalling standards were in common use?

DTMF (ITU-T Q.23 and Q.24)

Everyone’s heard DTMF (Dual Tone Multi Frequency). It’s the sound

your phone makes when you interact with one of those “Press 1 if

you are a new customer. Press 2 if you have a billing enquiry. Press

3…” systems. DTMF is still used by many fixed-line telephones

to set up a call.

In DTMF, each digit is encoded by playing a “high” tone and a “low”

tone. The low ones can be 697, 770, 852 or 941 Hz. The high ones

1209, 1336, 1477 and 1633 Hz.

None of the pairs in the audio match this, so it’s not

DTMF. Here’s an audio clip of what it would sound like

if we used DTMF signalling for the same number, with about the same

speed of tones:

CAS R2 (ITU-T Q.400—490)

CAS R2 uses a two-out-of-six tone scheme with the frequencies 1380,

1500, 1620, 1740, 1860 and 1980 Hz for one call direction and 1140,

1020, 900, 780, 660 and 540 Hz for the other. None of these are a

good match for the tones we heard. Besides, Pink is in the USA, and

the USA did not use CAS R2, so it’s not CAS.

This is what the digit signalling would have sounded like if

CAS were used:

SS5 (ITU-T Q.153 and Q.154)

SS5 also uses a two-out-of-six scheme with the frequencies 700, 900,

1100, 1300, 1500 and 1700 Hz. This matches most of what we can

hear, and SS5 is the signalling system most likely used for a call

from the USA to the UK in the early 1980s.

This is what the digit signalling sounds like in SS5, when

re-generated to get rid of all the other sounds:

SS7 (ITU-T Q.703—)

It can’t be SS7. Signalling system No. 7 (SS7) doesn’t use

tones at all; it’s all digital. SS7 is carried separately from the

audio channel, so it can’t be heard by callers. SS7 wasn’t in

common use until later in the 1980s.

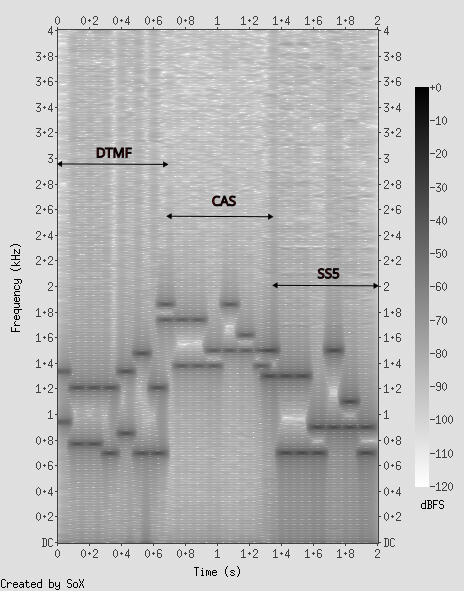

Comparing spectrograms

I made a spectrogram which combines all three signalling types on

the same chart. The difference between DTMF and SS5 is subtle, but

recognisable. CAS is obviously different.

Let’s feed the audio to some telecom hardware

I injected the audio file into a timeslot of an E1 line, connected

it to Corelatus’ hardware and started an ss5_registersig_monitor.

The input audio has a lot of noise in addition to the signalling,

but these protocols are robust enough for the digital filters in the

hardware to be able to decode and timestamp the dialled digits

anyway. Now, we know that the number signalling we hear was 044

1831. The next step is to analyse the frequencies present at the

start time for each tone. I re-analysed the audio file

with SoX, which did an FFT on snippets of the audio to find

the actual tone frequencies at the times there were tones, like

this:

sox input.wav -n trim 0.700 0.060 stat -freq

The results are:

| Time | Frequencies | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0—1200 ms | 483 Hz | dial tone |

| 729 | 1105 + 1710 | KP1 (start) |

| 891 | 1304 + 1507 | 0 |

| 999 | 1306 + 703 | 4 |

| 1107 | 1306 + 701 | 4 |

| 1215 | 703 + 888 | 1 |

| 1269 | 902 + 1503 | 8 |

| 1377 | 902 + 1101 | 3 |

| 1566 | 701 + 900 | 1 |

| 1674 | 1501 + 1705 | KF (stop) |

| 3800 | 2418 | Answer tone |

At this point, I’m certain the signalling is SS5. It uses the

correct frequencies to transmit digits. It uses the correct digit

timing. It obeys the SS5 rules for having KP1 before the digits and

KF after the digits. It uses a tone close to 2400 Hz to indicate

that the call was answered.

I’ve also listed the dial tone at the beginning, and the 2400 Hz

seizing tone at the end. SS5 also uses a 2600 Hz tone,

which is infamous for its use in blue box phreaking (telephone

fraud) in the 1980s.

How was the film’s audio made?

My best guess is that, at the time the film was made, callers could

hear the inter-exchange signalling during operator-assisted calls in

the US. That would have allowed the sound engineer to record a real

telephone in the US and accurately capture the feeling of a

long-distance call. The number itself was probably made-up: it’s too

short and the area code doesn’t seem valid.

The audio was then cut and mixed to make the dial tone overlap the

signalling. It sounds better that way and fits the scene’s timing.

Addendum, 18. December 2024: the audio also appears in ‘Young Lust’

It turns out that an extended version of the same phone call appears

near the end of ‘Young Lust’, a track on the album ‘The Wall’. Other

engineers with actual experience of 1970s telephone networks have

also analysed the signalling

in an interesting article with a host of details and background

I didn’t know about, including the likely names of the people in the

call.

It’s nice to know that I got the digit decoding right, we both

concluded it was 044 1831. One surprise is that the number called is

probably a shortened real number in London, rather than a completely

fabricated one as I suspected earlier. Most likely, several digits

between the ‘1’ and the ‘8’ are cut out. Keith Monahan’s analysis

noted a very ugly splice point there, whereas I only

briefly wondered why the digit start times are fairly regular for

all digits except that the ‘8’ starts early and the final ‘1’ starts

late.

Keep your files stored safely and securely with the SanDisk 2TB Extreme Portable SSD. With over 69,505 ratings and an impressive 4.6 out of 5 stars, this product has been purchased over 8K+ times in the past month. At only $129.99, this Amazon’s Choice product is a must-have for secure file storage.

Help keep private content private with the included password protection featuring 256-bit AES hardware encryption. Order now for just $129.99 on Amazon!

Support Techcratic

If you find value in Techcratic’s insights and articles, consider supporting us with Bitcoin. Your support helps me, as a solo operator, continue delivering high-quality content while managing all the technical aspects, from server maintenance to blog writing, future updates, and improvements. Support Innovation! Thank you.

Bitcoin Address:

bc1qlszw7elx2qahjwvaryh0tkgg8y68enw30gpvge

Please verify this address before sending funds.

Bitcoin QR Code

Simply scan the QR code below to support Techcratic.

Please read the Privacy and Security Disclaimer on how Techcratic handles your support.

Disclaimer: As an Amazon Associate, Techcratic may earn from qualifying purchases.